Is the Chicago Manual of Style a Sacred Text?

In which I'm weird about a style guide

Hello, everyone! I took off on Labor Day, so here is this week’s only blog post, in which I aimlessly discuss the Chicago Manual of Style.

First: What Is a Style Guide?

Copyeditors use style guides to help them edit texts for clarity and correctness. Much of what’s “correct” is more subjective than any of the grammar covered in a standard English class.

For example, which is correct?

A. I bought 18 peaches.

B. I bought eighteen peaches.

A. Every morning he took zinc, iron, and potassium.

B. Every morning he took zinc, iron and potassium.

A. What she most enjoyed — although she enjoyed so many things — was U.S. history.

B. What she most enjoyed—although she enjoyed so many things—was US history.

Et cetera. These examples just scratch the surface. But any of these could be correct, and the answers are determined by which style guide one's adhering to. Furthermore, the style guides are typically updated every 2–10 years, so the copyediting decisions one makes depend not only on the guide being used but on its edition.

The Chicago Manual of Style

There are many different style guides. The Associated Press Stylebook outlines how we write and copyedit journalism in the United States. The American Medical Association Manual of Style helps editors make decisions regarding medical research papers and books. And the Chicago Manual of Style is used for most of the humanities—for fiction and nonfiction alike. It offers guidance on everything from how to punctuate a sentence to how to cite a personal email. It’s over a thousand pages long, and as the Chicago website says, it is “the authoritative reference work for writers, editors, proofreaders, indexers, copywriters, designers, and publishers.”

It’s, like, a big deal.

If you're looking for a practical discussion of recent updates to the guide, let me redirect you to editor Erin Brenner's recent post. In it, she very sensibly writes, “Although no one wants to read every word of the 1,000-plus page behemoth that is CMOS…”

What proceeds in this post is, I guess, not very sensible.

Thoughts on Sea Moss (CMOS)

I read Chicago from cover to cover when I was earning my copyediting certificate in 2016. After that, I referred to it regularly for years as an educational copyeditor. When I became a freelancer last year, I read it from beginning to end all over again.

I have zero doubts that people can edit well without doing this—many well-qualified editors have found it strange that I have. So I don't advise that new/aspiring editors read it from start to end, although they should in fact actually read some of it—if you want to copyedit books written in US English, you need to own it and consult it often.

But for me personally, I can’t imagine doing my job without having read it all the way through.

When I read Chicago, it’s not because I’m trying to memorize every rule in it. I just don’t know how I’d copyedit if I didn’t have a firm grasp of the hundreds of topics it addresses. You don’t know what you don’t know—until you read Chicago, that is.

Another reason I’ve read and reread it? I like it. Whatever. I said it. It’s a solid read!

The other style guides—APA, MLA, and the UK Oxford Style Guide—are scantier than CMOS. CMOS is unique in both its breadth and depth. When I was a student and first learned about CMOS, I imagined that it was stuffy and prescriptive—and I think you can get that impression if you only ever use it as a reference book. Read it from start to end, however, and you'll discover it's often quite funny.

I recently looked up whether to italicize the names of artificial satellites; someone else had also once asked this question in the Chicago Q&A (because believe it or not, even after a thousand pages, editors still have more questions). And in this case, instead of answering, the folks at Chicago told the asker to just chill (my words) and decide something on their own for once. I had to smile.

It was written by people, and it's a human text.

In the newest edition, its writers updated the books it references. Lots of authors, many of whom are also editors, posted on social media that they were excited and surprised to see their own works get a nod in the style guide they use.

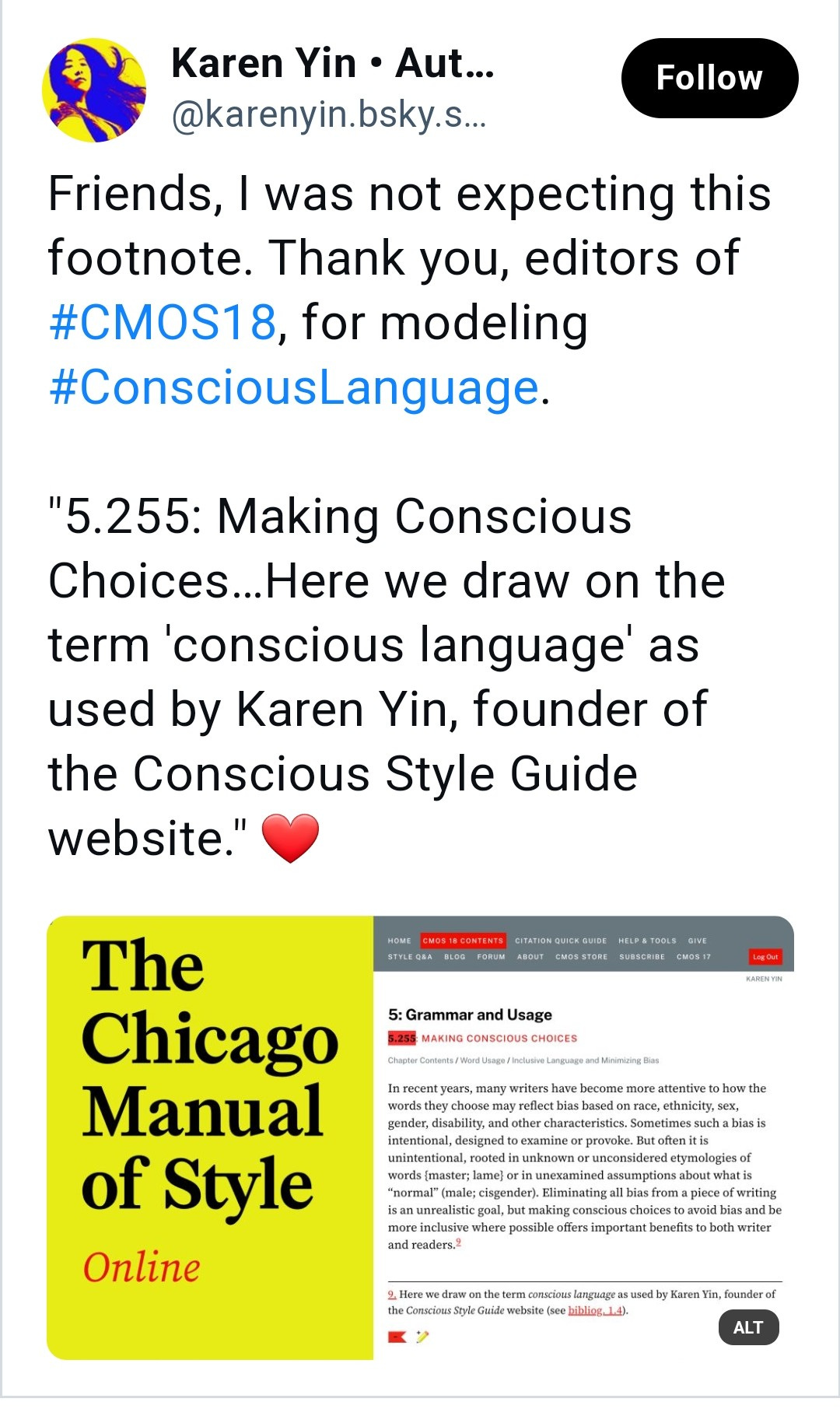

[Bluesky post reads: Friends, I was not expecting this footnote. Thank you, editors of #CMOS18, for modeling #ConsciousLanguage.

"5.255: Making Conscious Choices…Here we draw on the term 'conscious language' as used by Karen Yin, founder of the Conscious Style Guide website." ❤️]

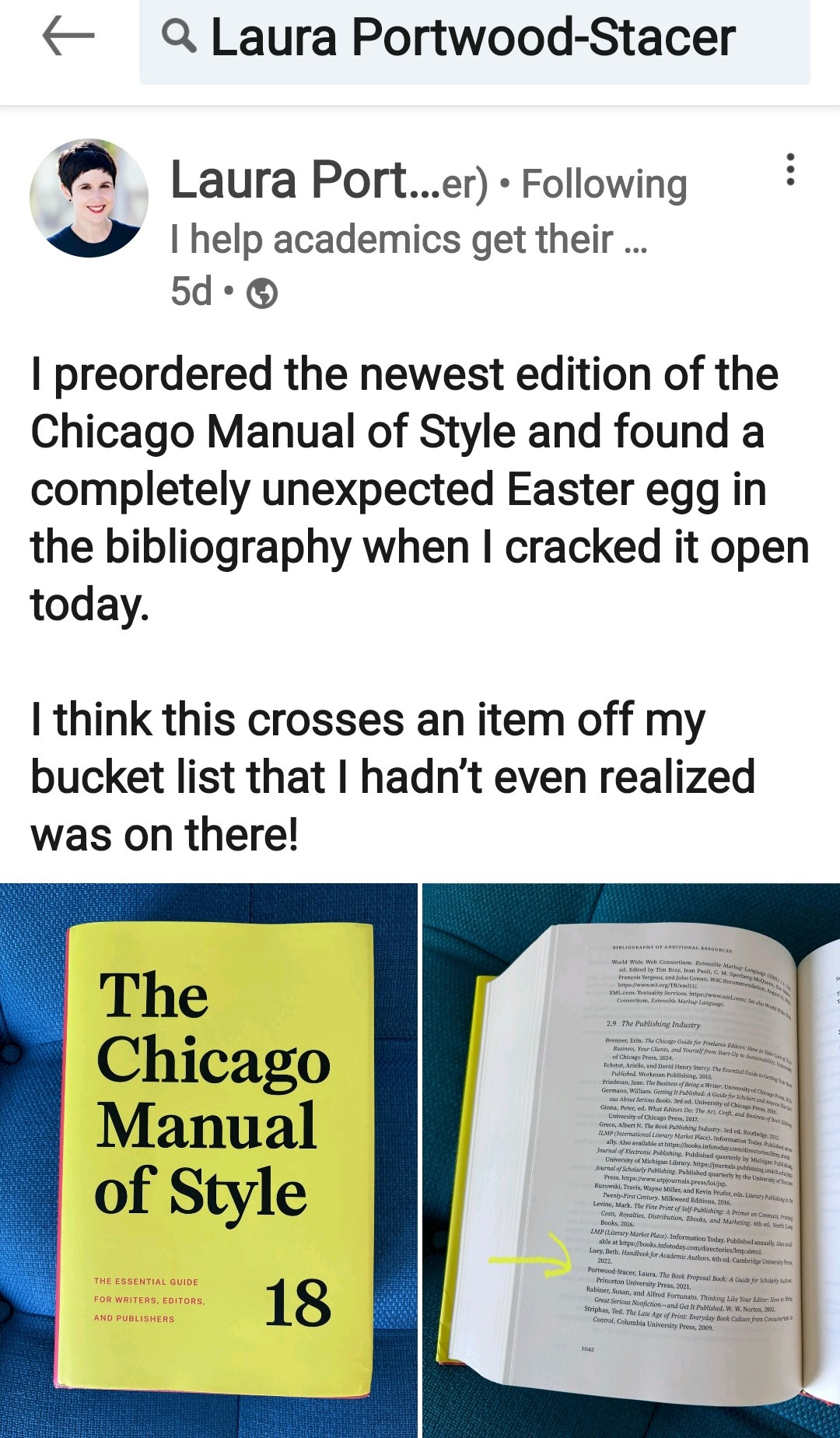

[LinkedIn post reads: Laura Portwood-Stacer: I preordered the newest edition of the Chicago Manual of Style and found a completely unexpected Easter egg in the bibliography when I cracked it open today.

I think this crosses an item off my bucket list that I hadn't even realized was on there!]

And now I’m going to get weird:

Yes, Chicago is a reference book. But it’s also the common link between the various folks of the North American book world. It reminds me of other times and texts that bind people over the long-term: the year I spent reading Catullus’s poems with my fellow Latin students; the seven-and-a-half years communities around the world spend reading one page of the Talmud each day; how for centuries aspiring civil servants across China memorized the verses of the Analects. Chicago is not an ancient or religious text, but its writers are plenty familiar with both. Chicago will neither enlighten nor scandalize you, but editors spend day after day talking about this one book, following and breaking its rules, learning from it, questioning it, debating it. So if editors make a big deal out of it, are we being stuffy nerds, or are we excited about this community we’ve formed and the values that inspire how we spend our days?

Editors don’t edit because we like red pens and being petty. We edit because we’re invested in helping the world talk to itself. We think your ideas matter, and we want to help others understand you. Chicago is a tool we use to make that happen.

I Am Old Now

The 18th edition of Chicago just came out. The 17th was released the year I began studying copyediting, so I am officially one of those editors—the kind who have been in the game so long that they respond to every copyediting question with all the possible answers of all the possible editions they've known. Heads filled with obsolete knowledge and a deep understanding of just how subjective this whole “language” thing is. Often, the glimpses older editors have given me of the 15th and 16th editions have made me wonder, Why don't we still do things that way?

CMOS 18, Where Are You?

Regarding the 18th: I love some of the changes the Chicago folks have made—the foremost being that we no longer need to include publishers’ cities in bibliography entries. The most ridiculous and unrewarding part of my job is that sometimes I have to google where a small Finnish publisher was located in the year 1953. I know information I'd rather not because of this requirement, like that the University of California Press moved from Berkeley to Oakland in 2014. In short: I’m very happy that I’ll no longer have to spend my one wild and precious life in this way.

Another change I love: If a complete sentence follows a colon, I should capitalize it! This feels correct to me, like scratching an itch I've long had.

What I don’t like, however, is the new online edition. Here’s what 17 looks like:

And here’s 18:

The coloring is painful on the eyes. The highlighter-green banner, the sans serif subtitles, and the gray fonts: These are all accessbility issues.

Other editors are offering tips on how to block the banner, view the webpage in greyscale, zoom in to enlarge the font, et cetera, but I’m disheartened that we now have to do this when we didn’t before. They had an online version that was accessible and easy to read. Why ruin this?

I’m hoping that they put the needs of editors first and change it. It seems right for them to walk the walk when they’re the ones who guide us on how to edit for equity and accessbility.

When You’re a Global Health Advocate, Arm Yourself with the Mighty Em Dash

One last thought before I go: Recently author John Green made a video about hyphens, en dashes, and our mutual true love, the em dash. Everything he says about the differences between them—and why the differences matter—is true according to the rules of CMOS. His deep enthusiasm, and the way he uses punctuation to more effectively fight for global health, makes me feel very slightly less embarrassed by my earlier comparison between my favorite copyediting style guide and great canonical works.

I've just completed what is hopefully the last big edit of my book about tuberculosis, and in the process, I've been reminded how much is contained within a dash. God, I love dashes. I love hyphens. I love en dashes. I love em dashes. … The deeper you dig into dashes, the more interesting they become. …

So, for example, in my book about tuberculosis, I might write, “And so even now, tuberculosis—a disease that has been curable for nearly a century—kills over 1.3 million people per year.” Now, I could have inserted that clause into parentheses, and that would have also been correct. … And listen, I'm not afraid of … parenthetical asides. It's just that I think em dashes often look and work better, for whatever reason.

“For whatever reason,” he says, but you can tell he knows the em dash is how you grab someone’s shirt collar and shake them through the page. Parentheses in the above example would make the fact he offers a sidenote; with em dashes, it becomes a rebuke and a call to action. And for that reason they are better for fighting tuberculosis, John Green—you’re entirely correct.

Until next time,

Hannah Varacalli

Copy & Developmental Editor

www.hveditorial.com